When teaching flatwater kayaking technique one of the cornerstone skills is that of how to stabilize the hull. As a coach and paddler I try to teach these concepts verbally, visually and kinethetically, but I've never tried to communicate this in a written manner, so here it goes.

As you move along a continuum from very stable hulls such as roto-molded recreational sit on top kayaks or sea kayaks (very high primary stability) to faster skis and K1s the consequences of bracing changes. With lots of primary stability you can brace wide, then as primary stability decreases the brace has to narrow down toward the long axis of the hull. In a high end ICF K1, the stability is found as close to the long axis as possible.

As with all sports, the kayak stroke requires a base of support which allows you to apply force. The more stable your base of support the more force you can apply. In paddle sports, a propulsive force accompanied by how fast you apply it generates the power to move you forward (i.e. speed).

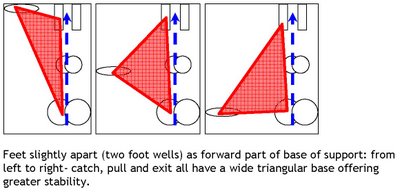

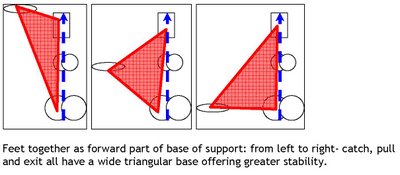

In kayak paddling, your base of support is a triangle extending from;

- your core/hips to,

- your paddle to

- where you contact the hull in front of your core.

- Some may even argue that it extends the entire length of the long axis of the hull that is in the water with proper technique.

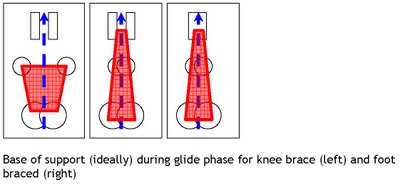

The core (1) and paddle (2) aspects of the base of support are relatively clear. The shape of the triangle changes as the hull moves past the paddle, but those two corners of the triangle (should) remain as part of the base of support. Only when you enter the glide phase is your base of support severely compromised by the lack of the paddle (2).

Looking at the location of that third point of contact in your base of support takes us forward from the hips. If you contact at the knees through bracing on the gunwales or cockpit your base of support is a short triangle.

Theoretically you will not be able to transfer much power to the hull while the paddle is in front of the hips as your base of support is quite narrow and far from the long axis of the hull.

Theoretically you will not be able to transfer much power to the hull while the paddle is in front of the hips as your base of support is quite narrow and far from the long axis of the hull.

Very skilled surfski and K1 paddlers are able to move that long axis from side to side very slightly to their advantage when using good technique.

Very skilled surfski and K1 paddlers are able to move that long axis from side to side very slightly to their advantage when using good technique. If a paddler is braced to tightly in their hull, every movement the hull makes is transferred into the paddler, and vise versa. In flatwater, it is mostly paddler movement affecting the hull stability, but as the water gets rougher the hull movement will increasingly affect the stability. This is most noticeable in steep side waves where the hull is pulled up and pushed down the wave face causing a fair degree of roll. If the hull rolls independently of the paddler there is little effect on stability, but when the paddler moves with the hull the centre of gravity moves further and further away from the centre of the base of support until balance is lost.

If a paddler is braced to tightly in their hull, every movement the hull makes is transferred into the paddler, and vise versa. In flatwater, it is mostly paddler movement affecting the hull stability, but as the water gets rougher the hull movement will increasingly affect the stability. This is most noticeable in steep side waves where the hull is pulled up and pushed down the wave face causing a fair degree of roll. If the hull rolls independently of the paddler there is little effect on stability, but when the paddler moves with the hull the centre of gravity moves further and further away from the centre of the base of support until balance is lost. In surfski and kayak paddling you see this very often in novice paddlers to rough water who flatten their stroke to widen their base of support accommodate their moving centre of gravity, and speed up the stroke to minimize the time spent without the paddle in the water for support (at the expense of propulsion).

In surfski and kayak paddling you see this very often in novice paddlers to rough water who flatten their stroke to widen their base of support accommodate their moving centre of gravity, and speed up the stroke to minimize the time spent without the paddle in the water for support (at the expense of propulsion).Further complicating the balance of a kayak in rough water is the effect of visual feedback. If a paddler looks at the water immediately around the hull or the hull itself, and uses this for balance feedback, the paddler will compromise their balance by moving with the perceived motion of the wave front(s) not simple allowing their centre of gravity to move up and down with the wave(s) passing under the hull and accommodating any challenges presented by the wind on the hull and paddler.

Anyways, just thoughts and theories.

Alan Carlsson

Alan CarlssonEngineered Athlete Services

No comments:

Post a Comment